Learn the Story of the Black Farmers Who Grow Equal Exchange Pecans

When you own the land you farm, you decide what to plant, when to harvest, and which maintenance methods to use. More importantly, you’re the one who controls your own livelihood. For Black farmers in the United States, land ownership is tied to freedom. But systematic racial discrimination has pushed many out of agriculture. Equal Exchange’s partners at New Communities, who supply our fair trade pecans, know the power of land — and these challenges — firsthand. They farm in southwest Georgia, in one of the poorest parts of the state. Over the organization’s fifty year history, these tenacious farmers have experienced more than their share of hardship and prejudice. Yet today, they are still farming and looking to the future.

Land and justice for Black Americans

Shirley Sherrod, Vice President for Development at New Communities Inc., as well as former USDA Georgia State Director for Rural Development, says that coming out of slavery, Black people knew that owning land was important “to help lift the family out of poverty.” By 1910, Black people owned more that 14 million acres of land. Black farmers in the South played an important role in the Civil Rights Movement. Their relative wealth meant they could bail protesters out of jail. And, as independent businesspeople, they could take action without worrying about what the boss would think.

But holding on to their acreage and turning a profit has proved to be an uphill battle. Black farmers in America encountered – and still encounter — bias in countless ways, from institutions and from individual neighbors alike. Sherrod told us that farmers she knew weren’t able to depend on fair grading for crops like peanuts. Many processors wouldn’t work with them and buyers might offer artificially low prices. White dominance at all levels of government in the South meant that Black farmers’ interests were not protected. They faced discrimination from the banking system. They had a hard time accessing loans and credit. In consequence, they learned to rely on each other.

New Communities: Built together

New Communities, established in 1969, put cooperative values into action from the start. Shirley Sherrod says that she and the founders realized they needed to build something of their own in order to “use the skills they had to make life better.” Her husband, Charles Sherrod (who was also a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) went to Israel with seven others to study the kibbutz model. They then designed New Communities as America’s first community land trust, and it was owned and operated by Black farmers. At almost 6,000 acres, it was the largest parcel of land owned by Black people in the whole country.

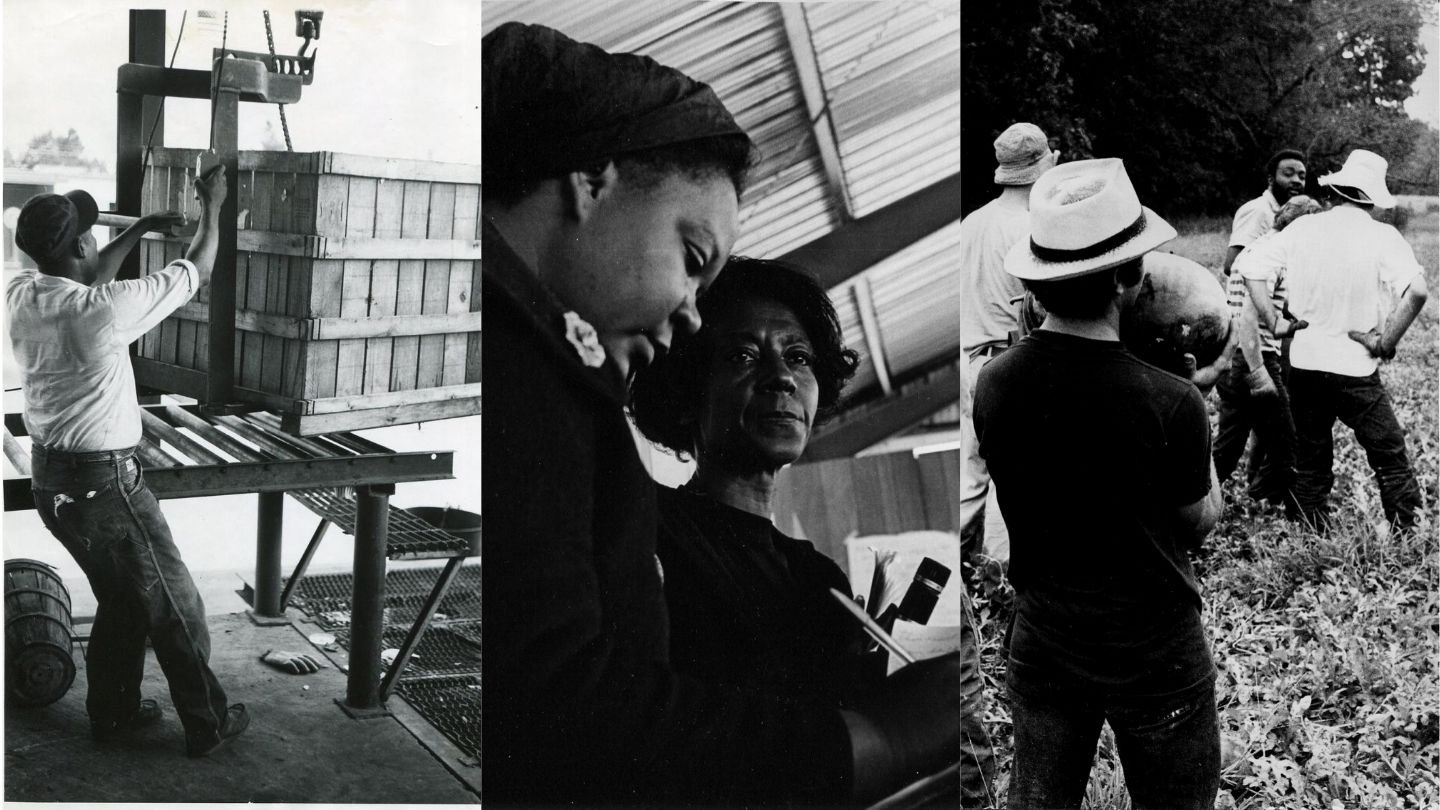

The farmers there raised hogs and grew staples like peanuts, soy and corn. They were some of the first in the area to cultivate Muscadine grapes. In addition to devoting land to crops, the founders planned for a real community that would someday include villages, industry and schools.

Shirley provided these undated pictures from New Communities’ past.

The Office of Economic Opportunity promised New Communities money and gave them a planning grant. But protests from white neighbors convinced the governor at the time, Lester Maddox, to veto federal money that might benefit their project. The local opposition they faced was constant. Once, Shirley Sherrod says, someone sabotaged their liquid fertilizer delivery, and they didn’t find out until the crops came up.

The farmers persevered. By the early ‘70s, they were selling watermelons to Safeway. But in the middle of the decade, drought hit the area. Like many of their white neighbors, New Communities applied to the Farmer’s Home Administration for an emergency loan. Sherrod remembers someone at the agency telling them straight out: “You’ll get one here over my dead body.”

Unlike the applications of other farmers, theirs was denied. Multiple years with continuing drought was too much, and by 1985, New Communities was in foreclosure. The new owner used digging equipment to push all existing buildings into giant holes, as if he wanted to get rid of every trace of what New Communities had built.

Confronting Black land loss

Sherrod turned her energy to working on the problem of Black land loss and on organizing agricultural cooperatives for Georgia farmers. She worked through supply chain challenges to help Black growers sell pecans to Ben & Jerry’s and watermelons to Northern grocery stores via Red Tomato, a company run by Michael Rozyne, one of the original founders of Equal Exchange.

The farmers had to learn new cultivation skills to grow smaller seedless melons. On the day the five tractor trailers arrived to transport the first shipment, Sherrod found it almost too stressful to watch the pick-up. The farmers didn’t have a loading dock and were hauling fruit from the field. But they got the trucks loaded and made that project work.

The role of the USDA

New Communities’ owners weren’t the only ones who had lost their land. In 1920, there were 925,000 Black-owned farms in the US, but by 1975, only 45,000 remained. Today, just 1% of rural land is owned by Black Americans. Black land loss is a recent phenomenon; much of it happened within the span of memory of people alive today. Sherrod identified the USDA as the main culprit.

In 1997, Black farmers filed a class action suit against the USDA, Pigford v. Glickman. They alleged that the agency’s allocation of farm loans and aid between 1981 and 1996 was unfair. The USDA admitted to having discriminated against Black farmers and settled, agreeing to a payout of $1.2 billion in the first phase and over a billion in the second phase. “I was so busy helping farmers gather the information they needed for their claims to go to the lawyer,” Sherrod says. “I almost forgot about our loss.” New Communities filed its own claim in 1999. The hearings, appeals and reviews went on for a full decade. Finally, in 2009, New Communities was awarded $12 million.

New Communities’ new start

Some of the original founders had scattered over the years, but Sherrod and others got busy finding land in the area of Albany, Georgia. They located an amazing property just outside the city limits: Cypress Pond Plantation, 1,638 acres once owned by the largest slaveholder and richest man in Georgia. He had owned nine plantations in total, but kept the largest number of enslaved people at Cypress Pond. “I had some problems with that, initially,” Sherrod admitted, “but I got past it, because I started thinking, what a statement for our people, that this property can go from a slaveowner to descendants of slaves.”

Pecan cultivation

At one point, most of the land had been planted with pecan trees, but when New Communities took over, only 85 acres of pecans remained. Sherrod recalls, “When I looked at the trees, all the leaves were gone and I didn’t think anything was there.” Luckily, they found some outside support — Hilton Segler, a white man who was an expert on pecan production and helped any way he could. Segler trained one of New Communities’ people on site, passing on his knowledge. “We planted an additional 115 acres to make it 200 acres,” Sherrod says. “We have young trees that are really, really producing.”

Sherrod contacted Rozyne, and he connected her to Equal Exchange. And Segler was able to line up a pecan processor, so they could begin selling nuts. Today, farmers at New Communities are growing satsuma oranges and Muscadine grapes for market. And this year, they’re growing 30 acres of vegetables to help deal with food insecurity in the local area. But pecans remain their major crop. Last year, Equal Exchange bought all of their pecan halves and helped find a buyer for the pieces that are a result of the shelling process. Sherrod says their business is growing. “Without Equal Exchange, I am not sure of what we would have done because just like in the past, we would have been locked out of markets that actually would help bring in some income.”

Black Farmers’ problems aren’t over

Black farmers still confront bias today. Younger people who want to get into agriculture often have trouble acquiring land. “The fact is,” Sherrod says, “it’s hard to get a white farmer to sell to a Black farmer, even today, in this area.” White farmers are still the ones with all the information and political clout; she wants to see policies that create ways for Black farmers and members of other racial minorities to be more involved.

And the problems with the USDA aren’t over. After the Pigford ruling, those who had been disadvantaged in the past were supposed to get priority, but it never happened, according to Sherrod. “Farmers who were successful with their claims were supposed to get debt written off.” While the general public might think that Black farmers got paid and the prejudice they faced is now in the past, that’s not the case. Sherrod says, “We haven’t seen much different happen.”

Moving toward healing

Still, Sherrod sees Cypress Pond as the perfect place for racial healing. Though only 800 acres are suitable for farming – much smaller than the thousands of acres that the original New Communities encompassed – she says, “we can do so much more with training, which is really needed at this point.” Through the Southwest Georgia Project, they provide regular training to about 100 farmers, hoping to expand production and share knowledge. Though not everyone can farm on the actual property, Sherrod says that this work ties them together.

How does Sherrod envision the future for Black farmers and collective organizations like co-ops and land trusts? “We’re going to have to identify opportunities for finding definite markets, because our people have been taken down roads,” she says. “People aren’t crazy. They want to be able to work together. But they have to see that there’s a possibility for success.” She’s pleased to see “younger farmers beginning to come on board who don’t know all that bad history … willing to actually work together to make some exciting things happen.”

Equal Exchange was lucky enough to have Shirley Sherrod join us as honored guest and keynote speaker at our 2020 Summit. This article is heavily based on Sherrod’s address. And we’re proud to partner with the farmers of New Communities to support their efforts as a model for future change. We think more people should know their story.

Shirley Sherrod, a Georgia native, resolved to stay in the South and work for change after her father’s murder by a white farmer. She participated in the Civil Rights Movement and helped to form New Communities, Inc., the first Community Land Trust in the United States.

Shirley has a B.A. in Sociology from Albany State University and a M.A. in Community Development from Antioch University. She has received many awards for her work in civil rights and as an advocate for farmers and rural residents. Shirley serves as the Executive Director of the Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education and Vice President for Development for New Communities, Inc.

References & Further Reading:

Douglas, Leah. “African Americans Have Lost Untold Acres of Land Over the Last Century.” The Nation.

Newkirk II, Vann R. “The Great Land Robbery.” The Atlantic.

Pickert, Kate. “When Shirley Sherrod Was First Wronged by the USDA.” Time Magazine.